From Pontarlier Redmond, known by the

code-name “Zulu”, set about establishing his C.E. organisation in Switzerland.

He was left to work on his own: In a memo to Colonel Dansey in London (10) he wrote that he had been sent to

Pontarlier “without any advice, orders or a single agent”. Nonetheless he did

“all the donkey’s work in establishing a Sw[iss] organisation, starting with

the V[ice] Consular System etc. also founding of the active C.E. work” which by

November 1917 had “bagged” 20 or 30 “Hun agents” from Switzerland and France.

The various Secret Service Organisations in Europe during the Great War were traditionally decentralised: agents would recruit sub-agents who would report to them, then the agent would report to his controller. A prime factor in this method of organisation was the ever-present risk of arrest; if caught, a sub-agent couldn’t bring down the whole organisation. In a neutral country like Switzerland it was also important for British Officials to try and remain within the law – removal of direct contact with agents helped in this regard.

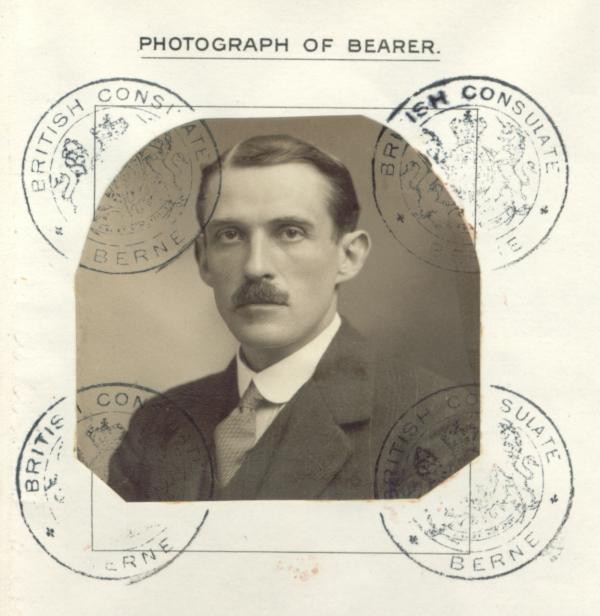

Redmond from his Passport issued 1st September 1916

However, on his arrival in Switzerland, Redmond immediately saw the advantages of using the British Vice Consuls in counter espionage, and in a Memorandum dated 5th November 1916, he proposed what he called “The Vice Consular Scheme”. His own experience had convinced him that agents should have access to the facilities the consuls offered. He also proposed combining Military Intelligence and Counter Espionage with Commercial attaché work: He thought it would be a waste of time, money and organisation NOT to combine these aspects: Agents in one area frequently came across work in the other areas that could easily be passed over if it didn’t come within their remit.

Although Redmond accepted it as a “sound principle” that Consular Officers shouldn’t jeopardise their position through espionage, he also observed that “a consul is in an exceptionally favourable position to obtain information of a commercial and a military character which might prove of great service to the country in this period of national stress.”

Here he had learnt from the German system: they had a Staff Officer and Staff attached to each consulate to collect information: The German Consul General employed some 122 men in the matter of espionage (not to mention the sub-agents and freelance workers) compared to 10 men employed by the French, and 8 by the British.

For his Vice Consular Scheme, Redmond proposed to

attach a Staff or other Officer to each consulate in the capacity of Commercial

Attaché. They would collect information through agents and then forward the

collected information to the British Consul General in Zurich. Military Intelligence and C.E. would

then be sent on to Pontarlier.

This would give 11 officers spread

throughout Switzerland collecting information and recruiting agents, close

enough to their sources to support them and verify the information they were

given.

Although the Vice Consular system was

brought into being, it never seemed to work entirely to Redmond’s expectations, as in his memos, he

frequently asked for more resources, or complained that the officers attached

to the consulates were being used for more mundane tasks such as passport

control.

There was also a continual friction between

different arms of the intelligence community in Switzerland: In April 1917 he wrote

to a superior named Anson “The P[ontarlier] organisation has never been used to

full advantage” and, in another recurring theme in his correspondence, he

complains that he was being sidelined. “It is hardly fair to delegate me, at

the very moment when the organisation is beginning to work efficiently, to the

rank of a simple instructing Agent.” (11)

It wasn’t just his superiors that were proving difficult – Redmond found it “almost impossible to get the men of the necessary qualifications out here” – “2nd Class” agents were easy enough to find, but they weren’t reliable enough to be put in touch with the Consuls direct, but were better suited to be used as sub-agents. (12)

For the better class of agent, Redmond appealed for men from England: “If a man has even a slight excuse of health, business or other reason for being in Switzerland, it would be many months before the Swiss begin to ask awkward questions.” (12)